Al McWilliams: Stone Drawings

After an unexplainable absence of over ten years from the Equinox Gallery's exhibition schedule, Al McWilliams returns with a quiet vengeance. Standing in the center of "Stone Drawings" the predominant experience is of harmony, a coherent, beautiful totality.

Seen as a single sustained gesture, "Stone Drawings" revolves like the expansion and contraction of the lungs, the continuous cycle of inhalation, exhalation, and the beginning of a new inhalation of breath. From in the round, through relief, to flat, and back up to relief, the ease and naturalness with which one set of works leads inexorability to the next, it's easy to end up walking the exhibition in circles following the endless round of rising and falling.

Seen as a single sustained gesture, "Stone Drawings" revolves like the expansion and contraction of the lungs, the continuous cycle of inhalation, exhalation, and the beginning of a new inhalation of breath. From in the round, through relief, to flat, and back up to relief, the ease and naturalness with which one set of works leads inexorability to the next, it's easy to end up walking the exhibition in circles following the endless round of rising and falling.

"Stone Drawings" begins with Sculpture #1 - Sculpture #5, five identical aluminum casts of a small, biomorphic sculpture, set in a line on a long, thin, steel table. They are the fullness of sculpture in the round, akin to that momentary holding of breath just before the contraction of exhalation.

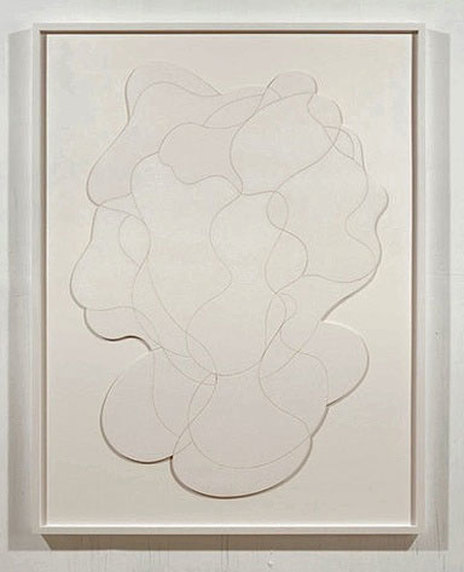

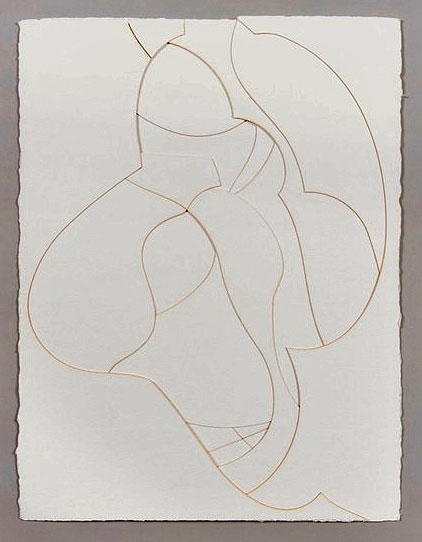

Next they are squeezed through the marble slabs of the Stone Drawings, to the single sheets of paper of the Big Paper drawings, to expand again, transformed into the stacked offcuts of the Stacked Paper (Heads). Each of the Stone Drawings is made from a single line drawing of the cast which is then used as a template to cut the marble. Two overlapped Stone Drawings are the template for the cuts of the Big Paper drawings. Finally, the offcuts from the sheets of 400 pound paper of the Big Paper drawings are stacked to make the Stacked Paper (Heads).

As the work in "Stone Drawings" is progressing from in the round, through flatness, and up to relief, it also makes its way between multiple and single views, and from "head" through abstraction and back to "Heads." Through these simultaneous movements, McWilliams makes "Stone Drawings" a brief history of sculpture of the past six hundred years.

From the fifteenth through the sixteenth centuries, even though sculpture was being finished in the round throughout this period, debate arose on the fundamental point of sculpture being either single or multisided. Opinions divided between sculpture being essentially flat and pictorial with a single privileged vantage point from which a passive viewer regarded the sculpture, versus sculpture having multiple sides with views of equal value and an infinite number of vantage points with the viewer an active participant in the life of the sculpture by having to walk around it. Not surprisingly, debate extended to the number of studies needed of a subject to produce a convincing sculpture in the round. Leonardo da Vinci was of the opinion that if properly executed, two would suffice, one from either side. Others, like Benvenuto Cellini, believed in the necessity of multiple studies depicting a subject's multiple views. By the second half of the sixteenth century the debate was settled, Mannerist sculpture was the vogue, and multifaciality the dominant practice.

The gradual compression of the work from sculptures #1 - #5 through the Big Paper drawings reflects the movement of sculpture from object to idea in the twentieth century. The early part of the century was characterized by the Cubist distillation of three dimensional reality to simultaneous, multiple views flattened to two dimensions. By the late 1960's, sculpture had been pressed so hard by Conceptualism that the object was squeezed out altogether and replaced by "idea." In an odd way, sculpture in the sixties saw a reemergence of Leonardo's belief in being able to fully understand an object from only two views. An idea with great currency amongst many of the founders of Minimal sculpture (and seen in the predilection for cubes and rectangular solids) was "sculptural gestalt;" the ability of grasping the entirety of a sculptural form from a single view.

As the work in "Stone Drawings" is progressing from in the round, through flatness, and up to relief, it also makes its way between multiple and single views, and from "head" through abstraction and back to "Heads." Through these simultaneous movements, McWilliams makes "Stone Drawings" a brief history of sculpture of the past six hundred years.

From the fifteenth through the sixteenth centuries, even though sculpture was being finished in the round throughout this period, debate arose on the fundamental point of sculpture being either single or multisided. Opinions divided between sculpture being essentially flat and pictorial with a single privileged vantage point from which a passive viewer regarded the sculpture, versus sculpture having multiple sides with views of equal value and an infinite number of vantage points with the viewer an active participant in the life of the sculpture by having to walk around it. Not surprisingly, debate extended to the number of studies needed of a subject to produce a convincing sculpture in the round. Leonardo da Vinci was of the opinion that if properly executed, two would suffice, one from either side. Others, like Benvenuto Cellini, believed in the necessity of multiple studies depicting a subject's multiple views. By the second half of the sixteenth century the debate was settled, Mannerist sculpture was the vogue, and multifaciality the dominant practice.

The gradual compression of the work from sculptures #1 - #5 through the Big Paper drawings reflects the movement of sculpture from object to idea in the twentieth century. The early part of the century was characterized by the Cubist distillation of three dimensional reality to simultaneous, multiple views flattened to two dimensions. By the late 1960's, sculpture had been pressed so hard by Conceptualism that the object was squeezed out altogether and replaced by "idea." In an odd way, sculpture in the sixties saw a reemergence of Leonardo's belief in being able to fully understand an object from only two views. An idea with great currency amongst many of the founders of Minimal sculpture (and seen in the predilection for cubes and rectangular solids) was "sculptural gestalt;" the ability of grasping the entirety of a sculptural form from a single view.

After the aesthetic severity of the two preceding decades, the eighties saw a general reintroduction of the figure into progressive sculpture, and the Stacked Paper (Heads) reintroduces the figurative into "Stone Drawings" after its own progression through abstraction. I say "reintroduces" because as much as sculptures #1 - #5 look nonrepresentational, their feeling is of more than a record of something squeezed in McWilliams's hand. For me it's a head (specifically Boccione's Futurist sculpture, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space), a feeling reinforced, I think, by the cycle of "Stone Drawings" finally being complete only when McWilliams recognizes a head in the Stacked Paper (Heads). References to other artists and their work, both representational and abstract, continue and include Arp's biomorphic sculptures and flat, painted reliefs in wood; Noguchi's flat marble sculptures; Matisse's paper cut outs; Brice Marden's loping lines; and finally, allusions to the contorted heads of Francis Bacon.

In an exhibition that otherwise proceeds in clear, rational steps, McWilliams has mysteriously chosen not to show the plasticene original from which the rest of the exhibition flows. His decision breaks with the transparency he establishes, but also signals that what is unseen (or maybe just not usually paid attention to) plays as large a part as what is seen. Sculptures #1 - #5 are each turned slightly, giving simultaneous multiple views similar to the overlapping views used to make the Big Paper drawings. The grayish veining of the marble Stone Drawings echoes the aluminum of #1 - #5. The sinuous, meandering cuts of the Stone Drawings contradict the veining, and the rigidity that we know the marble possesses. The edges of the Big Paper drawings are subtly discolored from the heat of the laser used to make the cuts. The offcuts from the Big Paper drawings were stacked until McWilliams recognized a head.

As programmatic as McWilliams has made the generation of one work from the next, the works themselves are not. Evocative and complex, they demonstrate that the tighter the restrictions, the greater the potential for subtle individual expression in their interpretation and execution. "Stone Drawings" is what might be called an artist's exhibition. It shows that appreciation of restraint and economy of means that comes with experience, and the knowledge of how small a gesture can be and yet still be meaningful.

As programmatic as McWilliams has made the generation of one work from the next, the works themselves are not. Evocative and complex, they demonstrate that the tighter the restrictions, the greater the potential for subtle individual expression in their interpretation and execution. "Stone Drawings" is what might be called an artist's exhibition. It shows that appreciation of restraint and economy of means that comes with experience, and the knowledge of how small a gesture can be and yet still be meaningful.