Across|Between|Within: Pierre Coupey's New Paintings

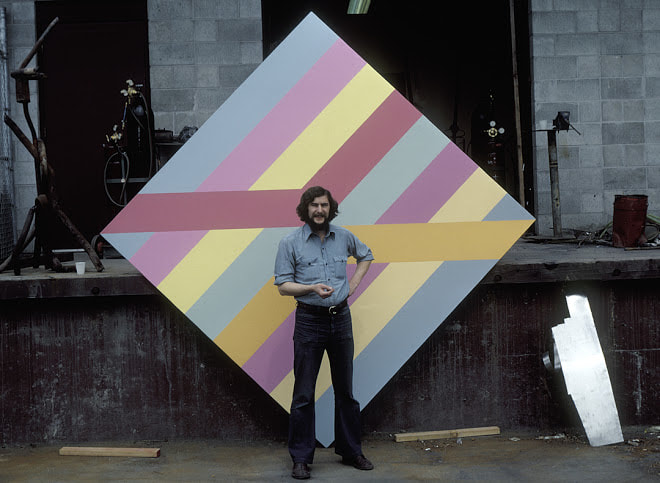

In an old photograph from 1969, Pierre Coupey stands in front of his painting Terminal Series II, one of the large, geometric abstractions making up his Terminal series. The painting is oriented on its point as a diamond, its surface divided into eight equal bands of smooth, un-modulated, hard-edged pastel color running diagonally. Two other bands run horizontally from corner to center. In style and application of paint it couldn’t be more different than the paintings of Across | Between | Within.

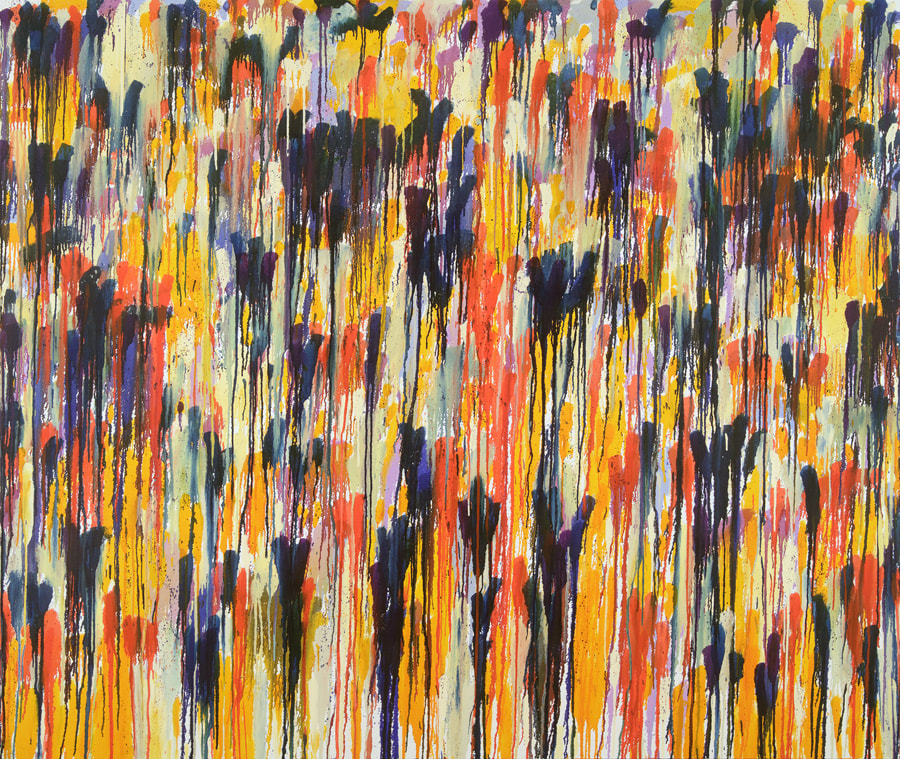

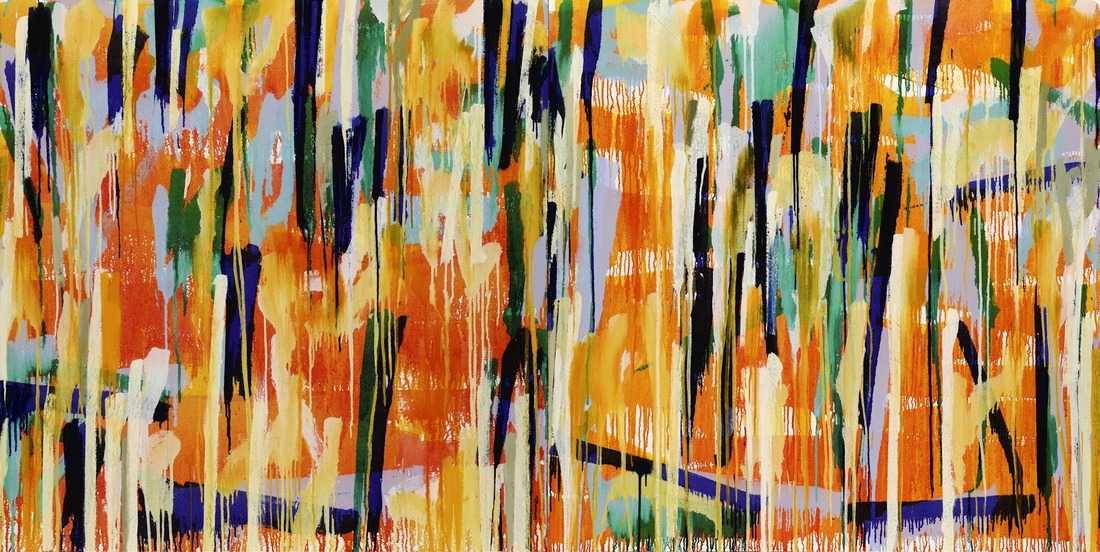

In these, the surfaces have been subjected to a relentless and methodical accumulation of strokes. If the Terminal paintings can be described as possessing a rigid clarity, these recent ones yield to an intuitive randomness. And to the dry austerity of the former, the latter are by contrast lush and wet. The paint’s viscous materiality has been so thinned that it runs down in rivulets creating a gravitational flow that makes the paintings look as if they could slide right off their supports: and yet. And yet all of the new paintings have a geometry and tension that holds them in place no less firmly than those of the Terminal series.

Although occupying opposite ends of Coupey’s oeuvre, the Terminal paintings and those of Across | Between | Within have this in common (and it is true of all Coupey’s paintings since 1968): before you see anything else, you see the paint. Equally true is that, before you get to one of his exhibitions, you never know what you’re going to see. This is because Coupey evolves from one way of painting to the next in an orbital manner; changes in brushwork, range of color, and composition from series to series don’t necessarily grow linearly and incrementally from one to the next. Sometimes they do, other times, as between the Tangle and immediately preceding Notations series, there are complete departures. And in still others aspects of earlier series reappear. There really is no telling what one can expect. Over the course of more than five decades as a non-representational painter, where repetition within limited variation is the norm (Jackson Pollock’s drips, Robert Ryman’s use of white, Sean Scully’s vertical and horizontal bands), Coupey has deliberately avoided settling into a signature style as he pursues new ways of painting with a relentless restlessness.

Because of the way Coupey’s energies and curiosity manifest themselves in paint, I am inclined to see parallels of method and aesthetic with his American contemporary Robert Ryman. The critic, curator, and academic Robert Storr describes Ryman as “a lyrical pragmatist... For Ryman, the art of painting is a search for particulars and distinctions; accordingly, composition is an experiment in the behavior of the medium and its sensory effect. Working hypotheses serve the painter but painting defies analysis, and its existence is defined only by the way of being of unique examples... Ryman paints in order to see things happen.”(1)

Painting to see things happen is also central to Coupey’s method, both as an intellectual position that explains why he paints, and as a description of the way he physically goes about making a painting. It has sustained him over a long career, and drives the changes in media and technique that characterize his search into diverse ways of non-representational painting. As Ryman has said, “there is never any question of what to paint only how to paint.”(2) Coupey and Ryman can both be regarded as realists in this respect; it is not the creation of illusion they pursue, but the presentation of a material and its range of application. But an explorer’s zeal for discovery is only half the explanation of why Coupey hasn’t limited himself in how he paints. The other is his distrust of ease and technical facility. Valuing intuition as an indispensable aspect of how he paints, once Coupey feels too comfortable with a way of painting, once intuition threatens to become habit, he moves away in another direction. He wants to be off balance, convinced that you have to work in a way that invites the unexpected to discover the unexpected, that only in a state of not knowing can something new, even profound, be found.

Although occupying opposite ends of Coupey’s oeuvre, the Terminal paintings and those of Across | Between | Within have this in common (and it is true of all Coupey’s paintings since 1968): before you see anything else, you see the paint. Equally true is that, before you get to one of his exhibitions, you never know what you’re going to see. This is because Coupey evolves from one way of painting to the next in an orbital manner; changes in brushwork, range of color, and composition from series to series don’t necessarily grow linearly and incrementally from one to the next. Sometimes they do, other times, as between the Tangle and immediately preceding Notations series, there are complete departures. And in still others aspects of earlier series reappear. There really is no telling what one can expect. Over the course of more than five decades as a non-representational painter, where repetition within limited variation is the norm (Jackson Pollock’s drips, Robert Ryman’s use of white, Sean Scully’s vertical and horizontal bands), Coupey has deliberately avoided settling into a signature style as he pursues new ways of painting with a relentless restlessness.

Because of the way Coupey’s energies and curiosity manifest themselves in paint, I am inclined to see parallels of method and aesthetic with his American contemporary Robert Ryman. The critic, curator, and academic Robert Storr describes Ryman as “a lyrical pragmatist... For Ryman, the art of painting is a search for particulars and distinctions; accordingly, composition is an experiment in the behavior of the medium and its sensory effect. Working hypotheses serve the painter but painting defies analysis, and its existence is defined only by the way of being of unique examples... Ryman paints in order to see things happen.”(1)

Painting to see things happen is also central to Coupey’s method, both as an intellectual position that explains why he paints, and as a description of the way he physically goes about making a painting. It has sustained him over a long career, and drives the changes in media and technique that characterize his search into diverse ways of non-representational painting. As Ryman has said, “there is never any question of what to paint only how to paint.”(2) Coupey and Ryman can both be regarded as realists in this respect; it is not the creation of illusion they pursue, but the presentation of a material and its range of application. But an explorer’s zeal for discovery is only half the explanation of why Coupey hasn’t limited himself in how he paints. The other is his distrust of ease and technical facility. Valuing intuition as an indispensable aspect of how he paints, once Coupey feels too comfortable with a way of painting, once intuition threatens to become habit, he moves away in another direction. He wants to be off balance, convinced that you have to work in a way that invites the unexpected to discover the unexpected, that only in a state of not knowing can something new, even profound, be found.

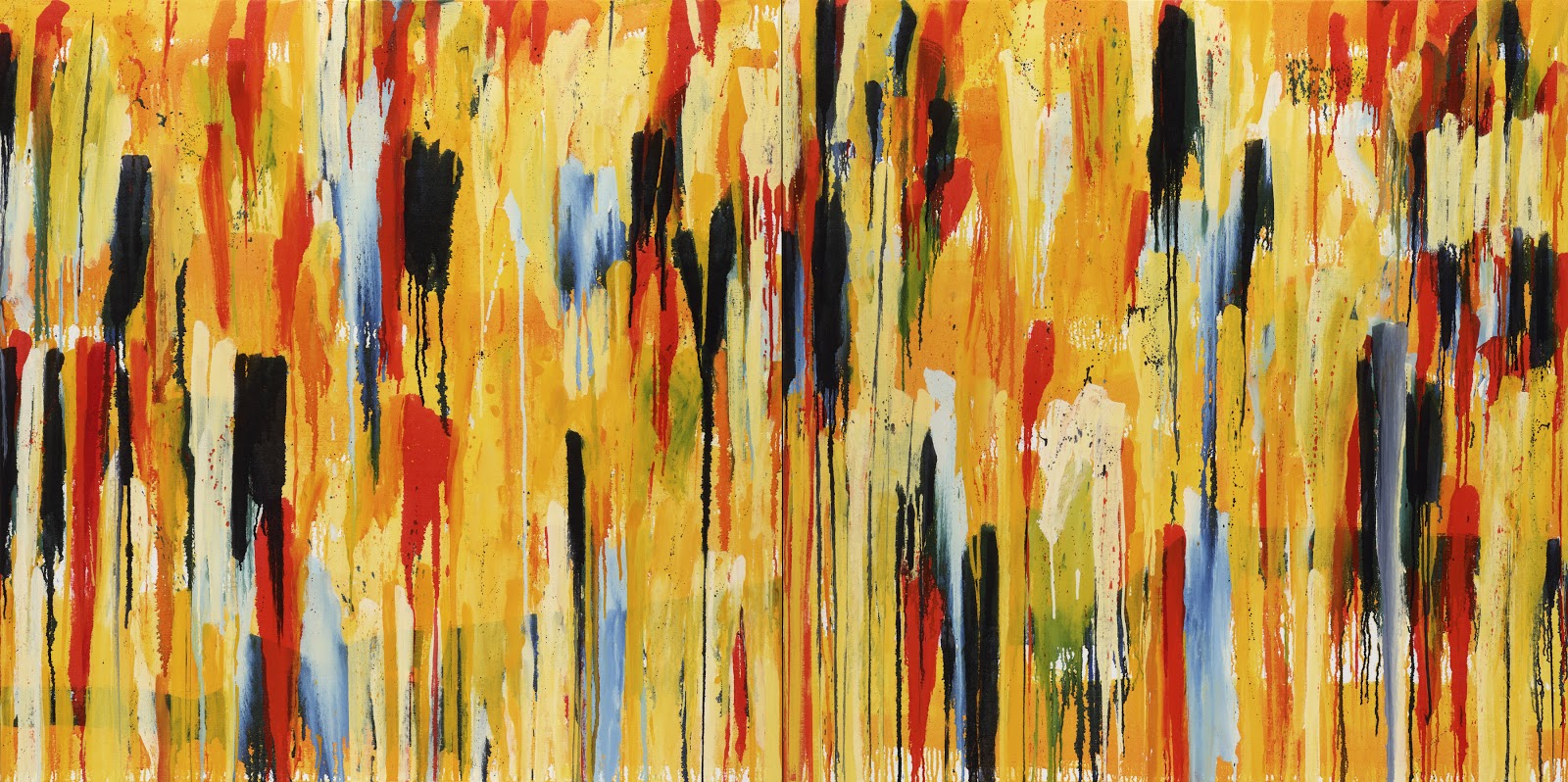

Before Ryman restricted himself to the exclusive use of white paints in the early 1960’s, he used other colors. One of these is the deep, warm, pumpkin orange he used for Untitled (Orange Painting), 1955, the one he considers his first professional painting. Coupey has never restricted himself coloristically in such a severe way, but in the first grouping of the Untitled paintings that I saw, the unmistakable impression, even with their blocks of blues, and greens, and whites (particularly numbers XX and XXI, but also Untitled XIX), was of orangeness. The effect was a visceral discomfiture that may have to do with the same thing that led to the adage amongst painters about the difficulty of orange as a color, and amongst poets to the joke that nothing rhymes with it as a word: and yet. And yet the paintings are visually sumptuous and undeniably beautiful.

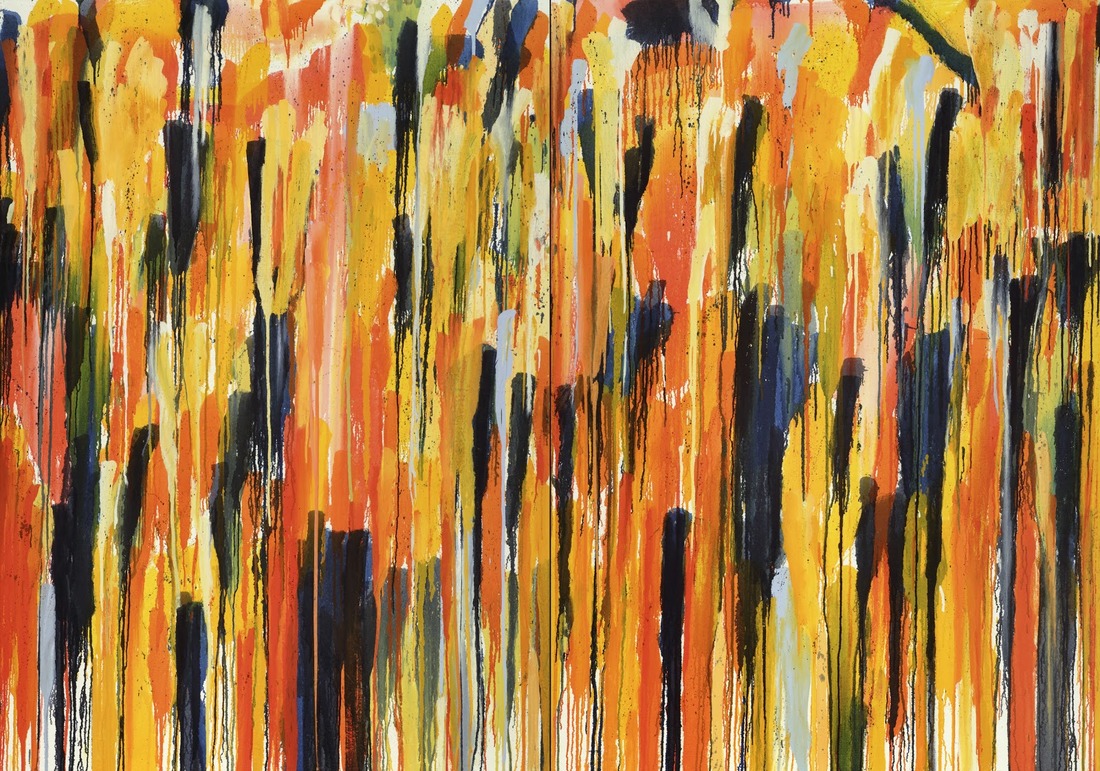

From Untitled XXII (Rock Pool, for PHC), through Untitled XXVII the colors shift to more reds and blues. Rock Pool I stands as an anomaly in the dominance of a single color: variations on an intense ultramarine blue.

Pinks and purples begin to appear in Untitled XXVIII and XXIX (Summer). By Untitled XXX (Spring), and even more so in Rock Pool II, they take over from orange as the dominant color impression, even though they don’t predominate in surface area covered. Purples, and a range of violets, are used more extensively than in earlier series. When purple made its previous appearance in the Notations series (1995), it looks to be an accidental mixing of colors on the canvas rather than a deliberate application from the palette. That might sound odd given we’re talking about a painter with red and blue right in front of him, but Coupey doesn’t use a palette, and rarely mixes colors before using them. The color on the canvas is the color from the tube. When colors do mix it is either on the surface, or when he uses the same brush to apply different colors.

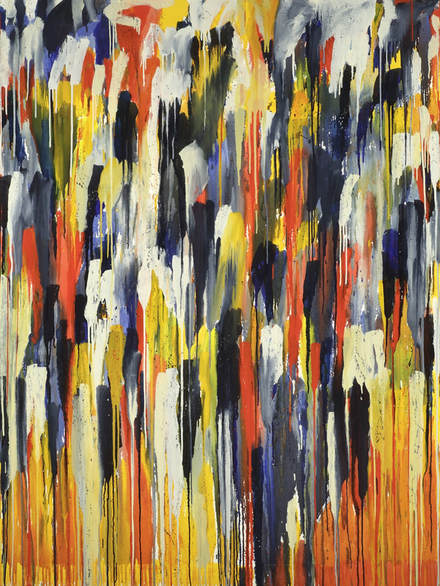

The Untitled paintings are composed by the steady accumulation of individual, parallel marks, some singular, some close enough together to form blocks. Their direction is almost always vertical and downward (as is the direction of the drips), following gravity. They are also layered at times, but the paint is thin enough that it never obscures what is below. Every mark is there to be seen. This should create the illusion of greater recession below the surface as should the natural optical play of cool colors receding and warm colors advancing. But the drips (traces of process rather than being expressive and emotive) keep the surface emphatic. Counteracting the vertical is the horizontal placement of stroke next to stroke.

The Untitled paintings are composed by the steady accumulation of individual, parallel marks, some singular, some close enough together to form blocks. Their direction is almost always vertical and downward (as is the direction of the drips), following gravity. They are also layered at times, but the paint is thin enough that it never obscures what is below. Every mark is there to be seen. This should create the illusion of greater recession below the surface as should the natural optical play of cool colors receding and warm colors advancing. But the drips (traces of process rather than being expressive and emotive) keep the surface emphatic. Counteracting the vertical is the horizontal placement of stroke next to stroke.

Though they vary in length, Untitled XXI is a good example of how the tops of the strokes are often aligned in approximately horizontal rows across the canvas’s width. Sometimes it’s a single stroke of color, other times a buildup of several together to make wider patches. The surface varies between dappled and block-like.

Beginning with Untitled XXVII, the strokes align less as continuous horizontal bands until in Untitled XXX (Spring), they begin to coalesce into loose, vaguely rounded clusters of colored strokes that open up spatial pockets onto a yellow ground. Even the drips can’t counteract this illusion of “looking through” to something beyond.

Rarely do the strokes continue to the bottom of the canvases. They stop roughly three quarters of the way down. The bottom quarter is composed mostly of the runoff from the painting that’s gone on above. This is where it’s most easy to see that something curious, even mysterious, is going on. Discernible beneath all the overlying vertical painting are long, broad horizontal strokes that must be the first that Coupey puts down on the canvas. They are like foundational marks that are gradually, but never completely covered over. Sometimes these horizontals are more obvious, as in Untitled XXVII, sometimes less so. In Untitled XXX (Spring), one hovers between strips of unpainted canvas just above the bottom edge of the canvas, only partially obscured by narrow rivulets. Because of its pronounced visibility and its separation from the clusters of strokes above, the horizontal reads as more of a traditional horizon line dividing illusionistic space. With the additional colors, the lighter touch in the application of paint, and the clustering of strokes, the sensation of Untitled XXX (Spring) is light, open, and rapturous.

When the Untitled paintings are exhibited, their hanging continues the cumulative, side-by-side procedure by which they are painted. Arrayed horizontally across the walls, the colorful individual paintings mimic the blocks of colored strokes that populate them, just as the blocks of strokes mimic the single strokes of which they’re composed. With the diptychs Untitled XVII and XIX, for instance, the analogy between painting and stroke is even more pronounced. Because of the horizontal arrangement of the strokes, the two canvases of the diptychs naturally line up well next to each other. They look like they were painted together as they hang. But look at the seams where they touch and at the marks on either side. You’ll see that they don’t always match. That’s because they are not always painted side- by-side in the order in which they are finally hung. Unafraid to adapt and change, Coupey will rearrange the canvases according to “the necessities of the rhythms, intervals, punctuations and rimes of forms and shapes and densities throughout the architecture of the piece” to reinforce their unity as a single painting.(3)

Rarely do the strokes continue to the bottom of the canvases. They stop roughly three quarters of the way down. The bottom quarter is composed mostly of the runoff from the painting that’s gone on above. This is where it’s most easy to see that something curious, even mysterious, is going on. Discernible beneath all the overlying vertical painting are long, broad horizontal strokes that must be the first that Coupey puts down on the canvas. They are like foundational marks that are gradually, but never completely covered over. Sometimes these horizontals are more obvious, as in Untitled XXVII, sometimes less so. In Untitled XXX (Spring), one hovers between strips of unpainted canvas just above the bottom edge of the canvas, only partially obscured by narrow rivulets. Because of its pronounced visibility and its separation from the clusters of strokes above, the horizontal reads as more of a traditional horizon line dividing illusionistic space. With the additional colors, the lighter touch in the application of paint, and the clustering of strokes, the sensation of Untitled XXX (Spring) is light, open, and rapturous.

When the Untitled paintings are exhibited, their hanging continues the cumulative, side-by-side procedure by which they are painted. Arrayed horizontally across the walls, the colorful individual paintings mimic the blocks of colored strokes that populate them, just as the blocks of strokes mimic the single strokes of which they’re composed. With the diptychs Untitled XVII and XIX, for instance, the analogy between painting and stroke is even more pronounced. Because of the horizontal arrangement of the strokes, the two canvases of the diptychs naturally line up well next to each other. They look like they were painted together as they hang. But look at the seams where they touch and at the marks on either side. You’ll see that they don’t always match. That’s because they are not always painted side- by-side in the order in which they are finally hung. Unafraid to adapt and change, Coupey will rearrange the canvases according to “the necessities of the rhythms, intervals, punctuations and rimes of forms and shapes and densities throughout the architecture of the piece” to reinforce their unity as a single painting.(3)

The Achilles’ Shields stand out for the obvious reason of being round. They draw attention to how much the strokes of the Untitled paintings repeat the shape of their supports and how a change in the shape of the support can change a painting’s tension. When the shape of the strokes, their arrangement, and the shape of the support reinforce one another it creates a stability that can be felt in the body as well as seen. The effect of the Shields’ round edges combined with the verticality of the strokes, and especially the drips, is of a barely held balance between compressive and centrifugal forces. Their strokes are generally less regular and ordered, and at the edges they are smaller and crowded together. Without actually measuring it’s hard to tell if they are more tightly packed together or only seem to be. These circles feel denser and heavier than their rectangular cousins. Compared to how gently the rectangles lay against the wall, the Shields really bang holes in it. Another general, but recognizable difference between rectangular and circular supports is the manner in which these shapes organize our viewing of them. The rectangle is a field. Our eyes scan its surface, straying out to its horizontal and vertical borders, and the corners at which they meet, to check for points of interest. With a circle, vision is corralled and the eye naturally moves to the center. There is no periphery, only an enormous focus.(4)

Rock Pool I, Rock Pool II, Rock Pool III, and Lac en Coeur signal Coupey’s most recent developments. The Untitled alignment of vertical strokes has evolved into a freer arrangement of irregular shaped strokes and blotches. In this way they are closer to the Achilles’ Shields, but their surfaces are less densely covered. When the eye moves into these gaps of unpainted canvas, the paint surrounding it advances off the surface and hovers. All that white canvas beneath the deep blue of Rock Pool I gives it the effect of being back lit. And more so than either the Untitled or the Shields, the compositions of the Rock Pools are more thoroughly all-over, showing a development from the chronologically earlier Stanzas.

Lac en Coeur and Rock Pool III diverge from Rock Pool I and II by combining the rectangular field with a circle’s focus by breaking a cardinal rule of composition not to make the center of the canvas a focal point of interest. If diagonal lines are drawn from corner to corner they cross at the canvas’ physical center and the radiating heart of the composition. Yet Coupey has playfully left this central point of interest rather empty: Lac en Coeur draws attention to its center by what’s not there and turns the usual relationship of periphery and center on its head. Loose brushstrokes surround patches of unpainted canvas before shooting off in all directions to pile up at the edges as seen in the Shields. The centrifugal feel of Lac en Coeur is partially explained by Coupey having painted it with the canvas laid flat on the floor so that he could circle around it, painting from all directions. Hung on the wall the effect is almost dizzying, like looking up at a domed ceiling.

Of the various paintings included in Across | Between | Within the Stanzas (painted on paper) have a special intimacy. The relative smallness of their size pulls one close for fuller appreciation, like whispering to encourage greater attention. Scale and the proximity at which one appreciates them aren’t the only qualities that account for the Stanzas’ intimacy, however. It’s also the quality of their marks, done with the wrist rather than with the arm and shoulder like the canvases. By and large they are gentler, softer, and give the illusion of greater depth of field.

Lac en Coeur and Rock Pool III diverge from Rock Pool I and II by combining the rectangular field with a circle’s focus by breaking a cardinal rule of composition not to make the center of the canvas a focal point of interest. If diagonal lines are drawn from corner to corner they cross at the canvas’ physical center and the radiating heart of the composition. Yet Coupey has playfully left this central point of interest rather empty: Lac en Coeur draws attention to its center by what’s not there and turns the usual relationship of periphery and center on its head. Loose brushstrokes surround patches of unpainted canvas before shooting off in all directions to pile up at the edges as seen in the Shields. The centrifugal feel of Lac en Coeur is partially explained by Coupey having painted it with the canvas laid flat on the floor so that he could circle around it, painting from all directions. Hung on the wall the effect is almost dizzying, like looking up at a domed ceiling.

Of the various paintings included in Across | Between | Within the Stanzas (painted on paper) have a special intimacy. The relative smallness of their size pulls one close for fuller appreciation, like whispering to encourage greater attention. Scale and the proximity at which one appreciates them aren’t the only qualities that account for the Stanzas’ intimacy, however. It’s also the quality of their marks, done with the wrist rather than with the arm and shoulder like the canvases. By and large they are gentler, softer, and give the illusion of greater depth of field.

Like the canvases, the Stanzas are predominantly painted in an all-over style, but they are more varied in the techniques employed: brushed and blotted, dripped and sprayed, scraped and collaged. Two stand out as particularly interesting: for their foreshadowing of Lac en Coeur’s central focus in a rectangular format; the contradiction between surface treatment (all-over) and composition (a center of focus at the center of the surface); their reflection of the tension between center and periphery; and their usefulness in illustrating the conceptual and procedural underpinnings of all the Stanzas. Stanza XVII has a blueish daub smack in its middle, a stationary anchor around which the rest of the brushstrokes shimmy and swirl, and to which the eye repeatedly returns for rest. It is a final exclamatory point, the pupil of an orange- rimmed eye. Stanza XX has a similar centrally placed mark, in this case a circular, blue ring.

Compared to what goes on in the center, what happens on the periphery is usually considered secondary or ignored altogether. Lac en Coeur is a major statement of Coupey’s painterly rebuke. The Stanzas go one step further to declare that the periphery can not only overshadow the center, but that a painting’s interest can be found even beyond its borders. Coupey recognizes that his paintings on canvas extend beyond the borders of their supports, not just as a metaphor, but literally. He acknowledges that the completion of a gesture (the last delicate drips and spray of larger marks made from the energy that travels from the sweep of his arm, or the flick of his wrist, through the brush, to the paint that leaves it) sometimes ends outside the painting, on the wall or floor. Examine the wall against which a painter paints, and chances are you’ll find a rectangular blank area (ordinarily occupied by a canvas) surrounded by splatters of color, and the floor below covered in drips. Coupey values these “lost paintings” as he does the entirety of the gestures that create them. The Stanzas are quite literally companion pieces to the paintings on canvas. They begin as sheets of paper either hung next to the canvases as they are being painted, or laying flat on the floor below. As a consequence some of their marks are made by chance, from overspray and dripping. Other marks are intentional, painted with the leftover paint from whatever canvas is being worked on. The result of this procedure is that the Stanzas wring every ounce out of Coupey’s paints and gestures. Once this stage of the process is complete Coupey goes back in with whatever additions and modifications are necessary until the Stanza is complete.

Much as Coupey makes paint and the act of painting the focus of his work, during the process of painting he admits to writing lists of all sorts of things that run through his mind, and that relate physically and materially to the piece he’s working on: “notes on color, what stage a painting is at, what the medium mix is, what poets or poems I’m thinking about, lists of possible titles, names of painters a given piece might be referencing, what landscape is urging itself upon me. What I’m fighting with.”(5) To the same extent as the paint, these lists are part of what can be seen (if not by the viewer, at least by Coupey) when the painting is looked at. When a painter paints, all of the art they are aware of, and all of their own experience is present; a ghostly parade aligned between the painting being worked on and the artist. Looking at the painting, the painter is stuck looking through all that it reminds them of. Coupey’s lists are catalogs of what he has to see through to see his paintings. And yet: to clearly see what a painting really looks like is an impossible (but nonetheless attempted) process of mentally shedding everything that is not paint. Here is an exact counterpart to Coupey’s process of painting that he describes as “ultimately the zen discipline of going blind, not seeing anything at all, not doing anything except being in the act of painting itself. Everything else falls away in that moment.”(6) When someone other than the artist looks at a painting they are in the same predicament of having to see through their own list, and it changes what is seen. “What we are,” says the mid-nineteenth century American essayist, lecturer and poet, Ralph Waldo Emerson, “that only can we see.”(7)

One of the things that becomes present to my mind, and that I have to see through when looking at the Untitled and Rock Pool paintings, is Robert Smithson’s rambling essay “A Sedimentation of the Mind” published in the September 1968 issue of Artforum. In the section entitled “The Climate of Sight,” Smithson characterized the kind of painting enjoyed by what he called the “wet mind,” which has a descriptive resemblance that I associate most closely to the feel of the Untitled and Rock Pool paintings.(8) In part, Smithson wrote his criticism of wetness as a rejoinder to the authority of Abstract Expressionism that still pervaded American art. It was also meant to mark a distinction with the kind of “dry,” less emotive art then being made by artists like Michael Heizer, Walter de Maria, and Smithson himself. In an odd twist, a year after its writing, and at the same time and place that Coupey was painting his very much “drier” Terminal Series, Smithson was visiting Vancouver, creating Glue Pour, his own version of liquidy, emotive art (dumping a drum of glue over a small embankment near UBC). The same quality of wetness that brings Smithson to mind, combined with the side by side arrangement of unblended strokes of color, brings Eugene Delacroix’s 1822 painting Bark of Dante before my eyes. Dante and his poet-guide Virgil sail through the waters of the underworld surrounded by the damned souls of wicked Florentines. On the torso of the woman at the right foreground, each droplet of water is composed of individual slashes of red, yellow and green pigment, side by side, which at a short distance blend together to create an effect of glistening wetness. My list also includes: Jasper Johns, Phillip Guston, Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Louis, Cy Twombly, Claude Monet. With the Stanzas, I am most reminded of Pollock at his best (when he was using a brush).

Because of Coupey’s lists, I don’t believe his search for what paint can do, or what he can do with paint, is the whole point of why he paints and exhibits. Neither is the point to reveal what he’s discovered. Paint is not all that Coupey wants to show, it is not all that he wants us to see. Towards the top of a stairway in Coupey’s home is a small, original print by Goya, La Tauromaquia No. 2, Another Way of Hunting on Foot. Two men push spears deeply into a bull from opposite sides. One pushes into the neck, just in front of the bull’s left shoulder. The other pushes through the ribs between shoulder and hip. The bull is down on one knee, mortally wounded and effectively pinned in place. By their wide-legged stance, the two men are equally immobilized, all three held in place until death. Had these actions been performed in a bullring as tauromaquia suggests, they would be part of a ritualized performance that, like it or not, has an important place in Spanish culture. But the scene does not take place in a bullring, it takes place in a nondescript, but pleasing landscape. Neither is it a hunting scene, even though Goya titles it otherwise. Performed outside of these contexts, what Goya depicts is a brutality reminiscent of his Disasters of War, as if Spain herself were being slaughtered. Bearing witness by recording brutality is one side of maintaining one’s humanity and standing against violence.

On the other side is creating beauty. Both are principled responses that stress art having a moral component, artists having personal responsibility, and what used to be called humanism. Motivated by a righteous indignation and the conviction that art can be serious, profound and life affirming rather than life denying, Coupey opts for an aesthetic of resistance. William Carlos Williams’ poem To a Dog Injured in the Street is one of Coupey’s touchstones in this regard. The poem concludes, “René Char / you are poet who believes / in the power of beauty / to right all wrongs. / I believe it also. / With invention and courage / we shall surpass / the pitiful dumb beasts, / let all men believe it, / as you have taught me also / to believe it.”(9) The critic and poet John Berger said very much the same in his essay The White Bird: “We live in a world of suffering in which evil is rampant, a world whose events do not confirm our Being, a world that has to be resisted. It is in this situation that the aesthetic moment offers hope.”(10) For Coupey, art at its best stands against violence as a defiant response to the outrages of barbarism committed against civilization. Without trying to see Coupey’s paintings through Coupey’s eyes, and without putting words into his mouth, what I see when I look at his paintings, and believe he is showing us, is an artist building a bulwark against Darkness, mark by mark, canvas by canvas.

Notes

1. Robert Storr, Robert Ryman, London / New York: Tate Gallery / Museum of Modern Art, 1993.

2. Robert Ryman, statement for Art in Process, Finch College Museum of Art, New York, 1969.

3. Pierre Coupey, from “Statements for Measures.”

4. In this analysis the relationship of the terms “field and focus” and “periphery and center” are being used analogously. The importance of the relationship between periphery and center in Coupey’s work seems to have grown in relevance, and relates him to the artist Robert Smithson. For Smithson, the dialectic between periphery and center marks his work and thinking as a central preoccupation. Although unrelated stylistically, there are a remarkable number of resonant connections between Coupey and Smithson, which are touched on throughout this essay.

5. Pierre Coupey, from “Statements for Measures.”

6. Pierre Coupey in correspondence with Dion Kliner, 2016.

7. Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nature, New York: Penguin, 2008.

8. “The wet mind enjoys ‘pools and stains’ of paint. ‘Paint’ itself appears to be a kind of liquefaction. Such wet eyes love to look on melting, dissolving, soaking surfaces that give the illusion at times of tending toward a gaseousness, atomization or fogginess. This watery syntax is at times related to the ‘canvas support’.” Robert Smithson, “A Sedimentation of the Mind: Earth Projects,” Artforum (September, 1969) 88.

9. William Carlos Williams, “To a Dog Injured in the Street,” The Desert Music and Other Poems, New York: Random, 1954. Williams was also Smithson’s pediatrician in Rutherford, NJ where they both lived.

10. John Berger, “The White Bird,” The Sense of Sight, New York: Vintage, 1985.

Compared to what goes on in the center, what happens on the periphery is usually considered secondary or ignored altogether. Lac en Coeur is a major statement of Coupey’s painterly rebuke. The Stanzas go one step further to declare that the periphery can not only overshadow the center, but that a painting’s interest can be found even beyond its borders. Coupey recognizes that his paintings on canvas extend beyond the borders of their supports, not just as a metaphor, but literally. He acknowledges that the completion of a gesture (the last delicate drips and spray of larger marks made from the energy that travels from the sweep of his arm, or the flick of his wrist, through the brush, to the paint that leaves it) sometimes ends outside the painting, on the wall or floor. Examine the wall against which a painter paints, and chances are you’ll find a rectangular blank area (ordinarily occupied by a canvas) surrounded by splatters of color, and the floor below covered in drips. Coupey values these “lost paintings” as he does the entirety of the gestures that create them. The Stanzas are quite literally companion pieces to the paintings on canvas. They begin as sheets of paper either hung next to the canvases as they are being painted, or laying flat on the floor below. As a consequence some of their marks are made by chance, from overspray and dripping. Other marks are intentional, painted with the leftover paint from whatever canvas is being worked on. The result of this procedure is that the Stanzas wring every ounce out of Coupey’s paints and gestures. Once this stage of the process is complete Coupey goes back in with whatever additions and modifications are necessary until the Stanza is complete.

Much as Coupey makes paint and the act of painting the focus of his work, during the process of painting he admits to writing lists of all sorts of things that run through his mind, and that relate physically and materially to the piece he’s working on: “notes on color, what stage a painting is at, what the medium mix is, what poets or poems I’m thinking about, lists of possible titles, names of painters a given piece might be referencing, what landscape is urging itself upon me. What I’m fighting with.”(5) To the same extent as the paint, these lists are part of what can be seen (if not by the viewer, at least by Coupey) when the painting is looked at. When a painter paints, all of the art they are aware of, and all of their own experience is present; a ghostly parade aligned between the painting being worked on and the artist. Looking at the painting, the painter is stuck looking through all that it reminds them of. Coupey’s lists are catalogs of what he has to see through to see his paintings. And yet: to clearly see what a painting really looks like is an impossible (but nonetheless attempted) process of mentally shedding everything that is not paint. Here is an exact counterpart to Coupey’s process of painting that he describes as “ultimately the zen discipline of going blind, not seeing anything at all, not doing anything except being in the act of painting itself. Everything else falls away in that moment.”(6) When someone other than the artist looks at a painting they are in the same predicament of having to see through their own list, and it changes what is seen. “What we are,” says the mid-nineteenth century American essayist, lecturer and poet, Ralph Waldo Emerson, “that only can we see.”(7)

One of the things that becomes present to my mind, and that I have to see through when looking at the Untitled and Rock Pool paintings, is Robert Smithson’s rambling essay “A Sedimentation of the Mind” published in the September 1968 issue of Artforum. In the section entitled “The Climate of Sight,” Smithson characterized the kind of painting enjoyed by what he called the “wet mind,” which has a descriptive resemblance that I associate most closely to the feel of the Untitled and Rock Pool paintings.(8) In part, Smithson wrote his criticism of wetness as a rejoinder to the authority of Abstract Expressionism that still pervaded American art. It was also meant to mark a distinction with the kind of “dry,” less emotive art then being made by artists like Michael Heizer, Walter de Maria, and Smithson himself. In an odd twist, a year after its writing, and at the same time and place that Coupey was painting his very much “drier” Terminal Series, Smithson was visiting Vancouver, creating Glue Pour, his own version of liquidy, emotive art (dumping a drum of glue over a small embankment near UBC). The same quality of wetness that brings Smithson to mind, combined with the side by side arrangement of unblended strokes of color, brings Eugene Delacroix’s 1822 painting Bark of Dante before my eyes. Dante and his poet-guide Virgil sail through the waters of the underworld surrounded by the damned souls of wicked Florentines. On the torso of the woman at the right foreground, each droplet of water is composed of individual slashes of red, yellow and green pigment, side by side, which at a short distance blend together to create an effect of glistening wetness. My list also includes: Jasper Johns, Phillip Guston, Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Louis, Cy Twombly, Claude Monet. With the Stanzas, I am most reminded of Pollock at his best (when he was using a brush).

Because of Coupey’s lists, I don’t believe his search for what paint can do, or what he can do with paint, is the whole point of why he paints and exhibits. Neither is the point to reveal what he’s discovered. Paint is not all that Coupey wants to show, it is not all that he wants us to see. Towards the top of a stairway in Coupey’s home is a small, original print by Goya, La Tauromaquia No. 2, Another Way of Hunting on Foot. Two men push spears deeply into a bull from opposite sides. One pushes into the neck, just in front of the bull’s left shoulder. The other pushes through the ribs between shoulder and hip. The bull is down on one knee, mortally wounded and effectively pinned in place. By their wide-legged stance, the two men are equally immobilized, all three held in place until death. Had these actions been performed in a bullring as tauromaquia suggests, they would be part of a ritualized performance that, like it or not, has an important place in Spanish culture. But the scene does not take place in a bullring, it takes place in a nondescript, but pleasing landscape. Neither is it a hunting scene, even though Goya titles it otherwise. Performed outside of these contexts, what Goya depicts is a brutality reminiscent of his Disasters of War, as if Spain herself were being slaughtered. Bearing witness by recording brutality is one side of maintaining one’s humanity and standing against violence.

On the other side is creating beauty. Both are principled responses that stress art having a moral component, artists having personal responsibility, and what used to be called humanism. Motivated by a righteous indignation and the conviction that art can be serious, profound and life affirming rather than life denying, Coupey opts for an aesthetic of resistance. William Carlos Williams’ poem To a Dog Injured in the Street is one of Coupey’s touchstones in this regard. The poem concludes, “René Char / you are poet who believes / in the power of beauty / to right all wrongs. / I believe it also. / With invention and courage / we shall surpass / the pitiful dumb beasts, / let all men believe it, / as you have taught me also / to believe it.”(9) The critic and poet John Berger said very much the same in his essay The White Bird: “We live in a world of suffering in which evil is rampant, a world whose events do not confirm our Being, a world that has to be resisted. It is in this situation that the aesthetic moment offers hope.”(10) For Coupey, art at its best stands against violence as a defiant response to the outrages of barbarism committed against civilization. Without trying to see Coupey’s paintings through Coupey’s eyes, and without putting words into his mouth, what I see when I look at his paintings, and believe he is showing us, is an artist building a bulwark against Darkness, mark by mark, canvas by canvas.

Notes

1. Robert Storr, Robert Ryman, London / New York: Tate Gallery / Museum of Modern Art, 1993.

2. Robert Ryman, statement for Art in Process, Finch College Museum of Art, New York, 1969.

3. Pierre Coupey, from “Statements for Measures.”

4. In this analysis the relationship of the terms “field and focus” and “periphery and center” are being used analogously. The importance of the relationship between periphery and center in Coupey’s work seems to have grown in relevance, and relates him to the artist Robert Smithson. For Smithson, the dialectic between periphery and center marks his work and thinking as a central preoccupation. Although unrelated stylistically, there are a remarkable number of resonant connections between Coupey and Smithson, which are touched on throughout this essay.

5. Pierre Coupey, from “Statements for Measures.”

6. Pierre Coupey in correspondence with Dion Kliner, 2016.

7. Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nature, New York: Penguin, 2008.

8. “The wet mind enjoys ‘pools and stains’ of paint. ‘Paint’ itself appears to be a kind of liquefaction. Such wet eyes love to look on melting, dissolving, soaking surfaces that give the illusion at times of tending toward a gaseousness, atomization or fogginess. This watery syntax is at times related to the ‘canvas support’.” Robert Smithson, “A Sedimentation of the Mind: Earth Projects,” Artforum (September, 1969) 88.

9. William Carlos Williams, “To a Dog Injured in the Street,” The Desert Music and Other Poems, New York: Random, 1954. Williams was also Smithson’s pediatrician in Rutherford, NJ where they both lived.

10. John Berger, “The White Bird,” The Sense of Sight, New York: Vintage, 1985.